Voter ID is NOT Documentary Proof of Citizenship. Here’s Why That Matters.

In this analysis:

Last month, New Hampshire voters headed to the polls only to be turned away or sent home to find their passport or birth certificate. This was the first test of New Hampshire’s new documentary proof of citizenship law, which mandates that all first-time voters in the state show proof of citizenship and residency.

“I had my birth certificate, a change of address from the US Postal Service — everything but my blood type and the kitchen sink — and I was told I could not register to vote,” New Hampshire resident Betsy Spencer said after a proof of citizenship law was enacted.

However, New Hampshire voters are not the only ones facing new barriers to vote. As of April 1 of this year, 22 states have considered legislation to impose new documentary proof of citizenship mandates, essentially requiring passports to vote, on voters – up from 14 states in 2024 and seven states in 2023. Many of these new laws are similar to the worst provisions in President Trump’s recent executive order on elections and the SAVE Act, which is currently pending in Congress.

Amid this surge in restrictive voting laws, one critical distinction is often blurred: the fundamental differences between voter ID and documentary proof of citizenship requirements. While two policies may sound similar, they have very different implications for voters, election administrators, and the future of our elections.

Passport Laws Are Far More Burdensome Than Voter ID

Voter ID laws, which are in place in some form in 37 states, are designed to ensure that the person casting a ballot is who they say they are. Voter ID laws rely on forms of ID that citizens commonly use in their daily lives, like driver’s licenses, military IDs, or student IDs.

Documentary proof of citizenship is a different story. These laws require a far less commonly-used document – usually a passport or birth certificate. Military IDs or REAL IDs generally do not meet this requirement since they do not verify citizenship, but rather lawful presence.

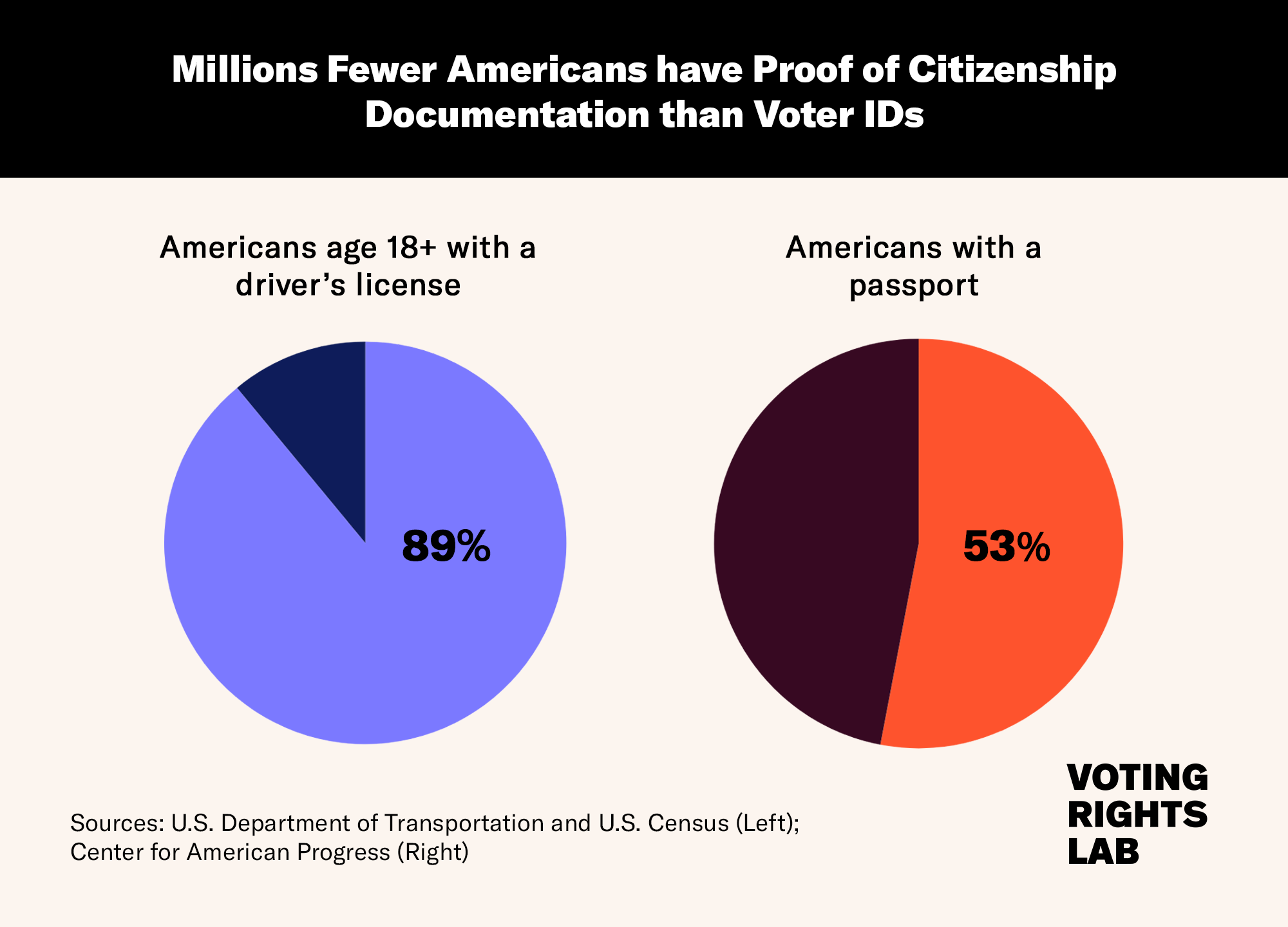

While consumer research shows as many as 89% of Americans over 18 hold a driver’s license, research shows only about half of voting-age Americans hold a U.S. passport. And for married women who took their spouse’s name, their birth certificates no longer match the names they use today – rendering them useless under these new requirements.

In addition, while voter IDs can be obtained relatively easily within a state, passports and birth certificates often require extensive paperwork and lengthy processing times from the federal government. States cannot issue passports, and while some may help residents obtain out-of-state birth certificates, the process can be both expensive and frustrating, especially for Americans born in states far from where they currently reside.

These burdensome new laws threaten to disenfranchise millions of U.S. citizens, particularly communities who do not have – or cannot afford to obtain – a passport. Voters in rural areas, low-income voters, and people of color—groups already more likely to face challenges obtaining ID—are especially at risk.

Passport Laws Create Bureaucratic, Costly Nightmare for Election Administrators

Most of the country uses voter ID as a way to verify voters’ identities. These systems have been in place for years, and each state has developed a system that works for their unique voting systems. Voter ID laws apply to both federal and state elections, creating a seamless process for election officials.

By contrast, proof of citizenship mandates require additional layers of documentation and verification. Most states would need to create two different voting lists for state and federal elections since federal law currently forbids requiring documentary proof of citizenship to vote in federal elections.

Passport and birth certificate requirements should be recognized for what they really are: exclusionary, costly, and burdensome policies that disproportionately impact vulnerable voters and create significant administrative headaches for election officials.

While voter ID laws have been successfully implemented in 27 states, documentary proof of citizenship laws have not: Arizona’s bifurcated system nearly denied over 200,000 citizens the freedom to vote in 2024 due to a database error. Likewise, when Kansas enacted a documentary proof of citizenship law, it inadvertently blocked over 30,000 eligible voters from registering in the three years it was in effect. The law was later struck down as unconstitutional by a federal appellate court.

There’s a Better Way Forward for Our Democracy

A key argument in favor of passport laws and similar mandates is that they will prevent noncitizens from voting in U.S. elections. However, the basic premise is flawed for two key reasons.

First, states already have rigorous safeguards in place to ensure that only U.S. citizens are voting in U.S. elections. These checks and balances, which are codified in both state and federal law, are enforced by bipartisan teams of election officials in every state. For over 20 years, Americans have been required to provide either a Social Security number or a state-issued ID (such as a driver’s license), which election officials use to verify citizenship status, when registering or voting for the very first time.

Second, every reliable study and audit has shown that claims of widespread voting by noncitizens are unfounded. There is simply no evidence to support these false claims.

Given the exclusionary and harmful impact of these laws, states considering these measures must answer a fundamental question: what are we really solving for?

If lawmakers are serious about securing our elections, there are practical and evidence-based ways to do it – without wreaking havoc on state election systems or preventing eligible citizens from voting. For example, state lawmakers and administrators can improve data sharing between state agencies to strengthen the process and leverage existing data. Election officials can ensure that voters are notified before their registrations are cancelled and that adequate timelines are in place for list maintenance. Lastly, we can pursue alternatives such as ERIC (the Electronic Registration Information Center) to ensure election workers have the highest quality data possible for keeping voter rolls clean and accurate.

Subscribe to our newsletters

Get regular insights and analysis from Voting Rights Lab, delivered straight to your inbox.