Report

How State Laws Complicate the Right to Vote While Incarcerated

Though many incarcerated citizens have the right to vote in principle, a number of legal and logistical hurdles make it difficult – and sometimes impossible – for them to cast a ballot. In many cases, incarcerated citizens may not even know they remain eligible to vote while confined, with resources that might inform them of their voting rights, election deadlines, and processes for casting a ballot likely to be out of reach. Because citizens’ ability to participate in the electoral process while incarcerated is often dependent on proactive efforts from community leaders, local election officials, and facility administrators, it is important to highlight the recent steps some states have taken to improve voting access for incarcerated citizens. In this month’s Hot Policy Take, we take a look at the current landscape of voting access for eligible incarcerated citizens, how states are addressing these significant barriers, and what lies ahead in this often overlooked policy issue.

Understanding Voting While Incarcerated

Certain incarcerated people are eligible to vote in all 50 states and D.C. This ranges from states where only pre-trial detainees who have not been convicted of a crime are eligible to vote, to jurisdictions where all incarcerated individuals retain their voting rights (in Maine, Vermont, and Washington D.C.).

Of the nearly two million people incarcerated in America, almost one-fourth of them (427,000 people) are in jail, as opposed to prison, and have not been convicted of the charge(s) for which they are incarcerated. They are presumed innocent in the eyes of the law. Nevertheless, for many reasons – including the money bail system – they remain detained in local jails while awaiting trial. These individuals are eligible to vote, so long as they are not already disenfranchised due to an existing felony conviction or other disqualifying factor under that state’s law.

It is important to note that voting while incarcerated is distinct from voting rights restoration – individuals who are detained and remain unconvicted of a disqualifying offense have not been legally disenfranchised. Unlike the issue of voting rights restoration, where changing state laws or constitutions is often required, disenfranchisement for many incarcerated citizens could be lessened simply by adopting policies that increase voter access in jails and other detention facilities.

For more information on the state of voting rights restoration, and the proliferation of efforts across states to restore the vote for those with past convictions, check out our March Hot Policy Take.

Logistical and Legal Hurdles for Incarcerated Voters

All too often, eligible incarcerated citizens face significant barriers to registering and casting a ballot, from obtaining ballot applications without internet access to complying with states’ ID or notary requirements.

Detention can be transitory. People can find themselves detained at random times during the election process – often for short periods of time. A person who is arrested days before a deadline to register to vote, request a mail ballot, return their mail ballot, or cure a minor error with their ballot may be effectively precluded from voting.

Rarely offered in-person voting opportunities, incarcerated individuals generally must navigate mail voting without the freedom enjoyed by most voters. Their ability to make calls, access the internet, or send and receive official mail is limited, making otherwise routine tasks sometimes insurmountable.

Few jurisdictions establish physical polling locations at detention facilities, which require coordination between the facility administrators and local election authority. Many states allow people to vote by mail from jail, but there are legal and administrative barriers to doing so. Below are some examples of the various complications incarcerated voters may face.

- Excuse for mail ballot: In four out of the 14 states where an excuse is required to vote by mail (Connecticut, Indiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee), detention is not expressly listed as a valid excuse for excuse-required mail voting. In New Hampshire, detention is only expressly listed as an excuse if incarcerated for a misdemeanor.

- Mail ballot application deadlines: If a person is arrested after the deadline for mail ballot applications, they may be de facto disenfranchised. Deadlines vary across the country from the 15th day before Election Day (like in Iowa) to the day before Election Day (like in Connecticut, Maine, and Minnesota).

- Cure opportunities: While incarcerated, a voter may have limited opportunities or options available to cure issues that arise with their ballot, given typically slower mail service in detention facilities, minimal inmate access to telephones or internet, and an inability to travel to an elections office to correct issues.

- Third party ballot return: Recent laws limiting access to third party ballot return, such as those in Texas and Florida, could mean that even a sworn member of law enforcement is unable to assist a voter returning their ballot.

- Resources and administration: Even where detention is an available excuse to receive a mail ballot, the ability to cast a ballot while incarcerated usually requires local election authorities or law enforcement to be proactive in creating policy and providing sufficient funding.

States Make Progress for Incarcerated Citizens

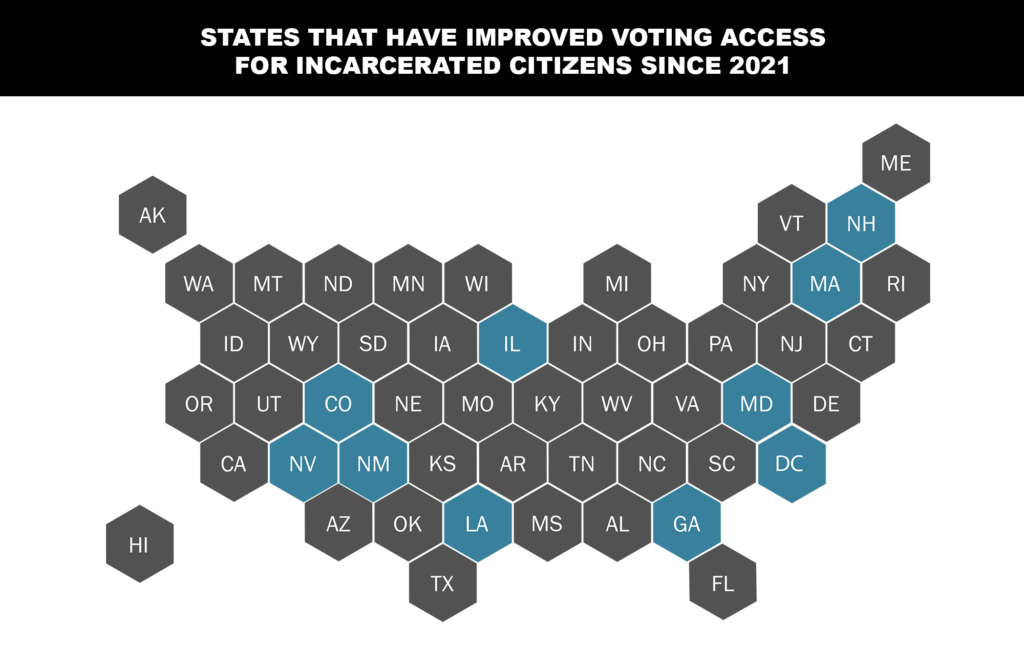

Between 2021 and 2023, nine states and D.C. have enacted 12 laws to improve voting access for those who are incarcerated – including four new laws enacted this year alone. The improvements to state law for incarcerated voters enacted since 2021 fall into three general categories: voter registration, mail voting, and in-person voting.

Improved access to voter registration

Maryland, Colorado, and Washington improved voter registration opportunities.

- A 2021 Maryland law now requires voter registration applications to be provided to eligible voters in jail 30 days before the registration deadline.

- As of 2023, in Colorado, counties that have issued electronic tablets to incarcerated voters must use those tablets to facilitate voter registration.

- In 2023, Washington’s state budget included $2.5 million to provide county grants to improve voter registration services and voting access in county jails. However, only a few counties in the state applied for the funding, and some local officials have openly expressed an unwillingness to assist incarcerated citizens looking to participate in elections.

Improved access to mail voting

Massachusetts and Nevada made it easier to vote by mail.

- Massachusetts created new requirements in 2022 related to incarcerated voters using mail ballots, including mandatory voter information and education, as well as voter assistance for requesting, completing, and returning forms and ballots. Under the law, jails (where feasible) must provide locations where voters can complete ballots in private and jail officials may not open or inspect any completed mail ballot (unless it is to investigate a reasonable suspicion of prohibited activity).

- A 2023 Nevada law requires each county or city jail to facilitate the casting of mail ballots.

Improved in-person voting

Illinois and D.C. made it possible for individuals to cast their vote in person while they are incarcerated.

- Illinois passed a law requiring counties with three million or more residents to establish temporary polling places in jails. (Nationally, jail-based polling places are less common, but here are seven examples that indicate this has been an effective solution that increased voting among incarcerated individuals.)

- D.C. passed a law this year requiring the board of elections to establish a vote center at a Department of Corrections facility where eligible incarcerated individuals can vote.

Ongoing Efforts

Some state efforts to expand – or restrict – voting access for incarcerated citizens are ongoing. Arizona and Texas provide two examples of the types of legislation states are considering.

In Arizona, the state legislature tried to restrict access for incarcerated voters in January by limiting mail voting in Arizona jails with H.B. 2325. The bill would have required them to apply for the process at least 180 days before Election Day and provide documentary proof of their U.S. citizenship (a requirement that has been deemed unconstitutional in other voting contexts). The bill ultimately stalled in the Arizona Senate over concerns about the legality of some of its restrictions. Meanwhile, in Texas this year, some state legislators have attempted to codify a successful 2021 program implemented to expand access for incarcerated citizens in Harris County, which gave eligible incarcerated voters who entered custody after the absentee ballot application deadline the ability to vote in person at the jail on Election Day. Two bills to enshrine this process into state statute failed to move in the legislature.

Conclusion

Improving voting access for citizens while they are incarcerated has gained attention from state legislators and administrators in recent years, but it remains an overlooked area of voting rights policy. Our team at the Voting Rights Lab sees vast opportunities to increase and protect access for incarcerated voters in most states through the implementation of legislative and administrative solutions.

The tide seems to be turning, with more and more bills introduced to address voting access disparities for incarcerated citizens. Despite some pushback, legislatures across a growing number of states have implemented solutions making it easier for incarcerated citizens to register, mail in their ballot, and vote in person. We hope – and expect – the forward momentum will continue.

Our team tracks legislation that would make it easier (or more difficult) to vote by mail while incarcerated, as well as bills that would create in-person voting opportunities in jails and prisons, in our State Voting Rights Tracker.

Power the State Voting Rights Tracker

In the last 3 years we have tracked and analyzed over 5,000 bills. With your support our team of policy experts can track election law and proposed legislation across all 50 states and DC.